Have you ever wondered why so much of today’s information still depends on screens, numbers, and alerts—formats that require users to actively interpret and respond?

Dolce is a small research project where I explore a simple question: How could interactions in the smart home feel more intuitive and human? Rather than relying on screens, apps, or voice commands, I wanted to test whether information could be delivered in a quieter, more natural way—one that fits directly into everyday actions.

Most people don't realize how much food they throw away every day—from leftovers to spoiled produce. It is estimated that 1/3 of all food produced for human consumption is discarded or wasted globally. When it comes to the consumer level, around 2/3 of spoiled food generated in the home environment is due to food not being used before it goes bad. Why is reducing food waste so strongly emphasized worldwide, yet so hard to practice in people's daily lives?

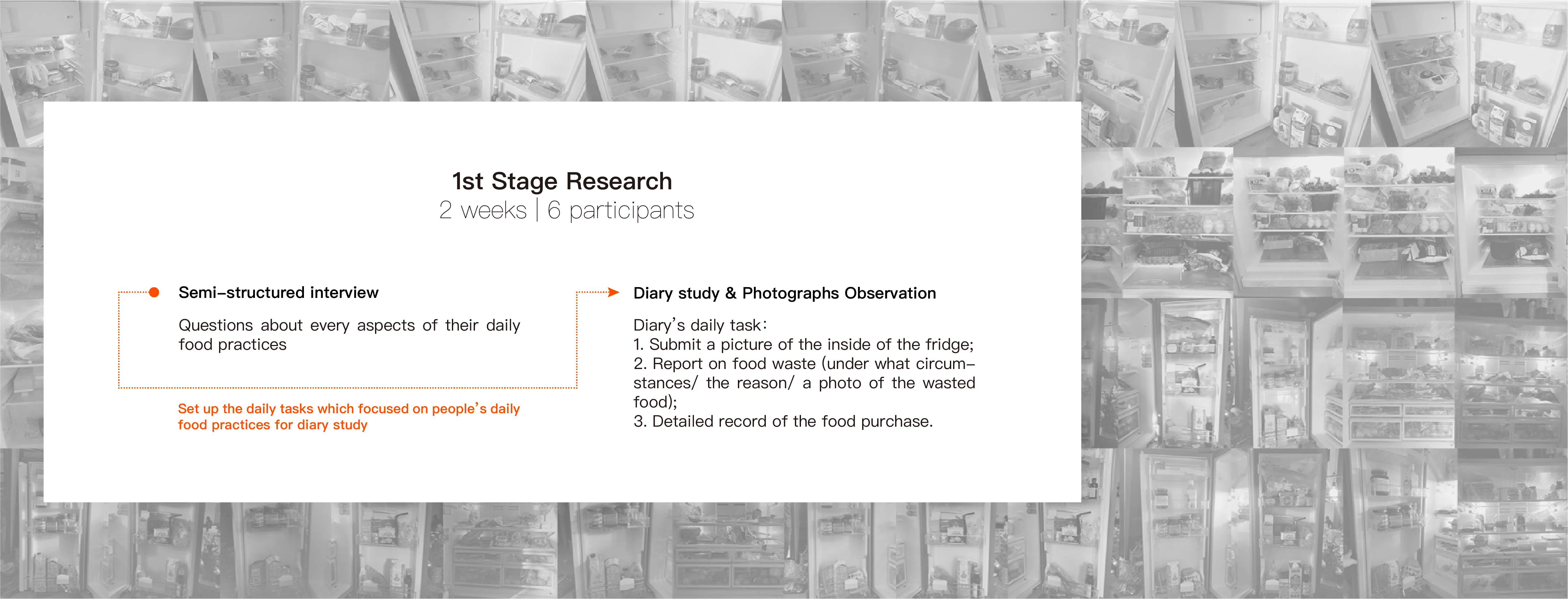

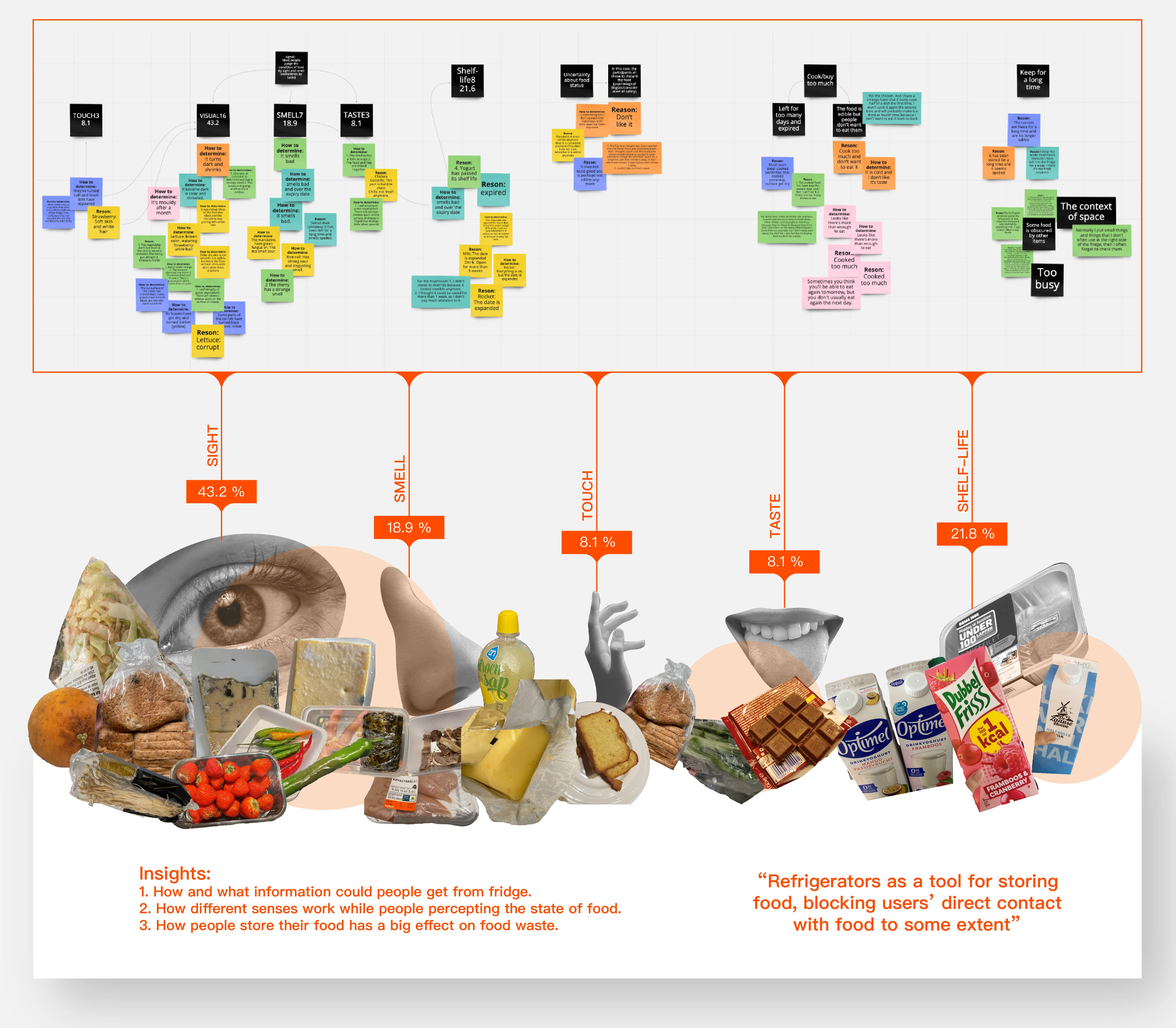

The Thematic analysis method was used to manually collate and analyze the data. Firstly, the photos of the fridge sent by the participants, the food discarded, and their self-responses were centrally counted and linked. Subsequently, I identified related notes, grouped them under initial subheadings, and then looked for overarching themes to create higher-level categories. These data collectively illuminated the frequency, categories, and decision-making processes participants employed when discarding food due to spoilage.

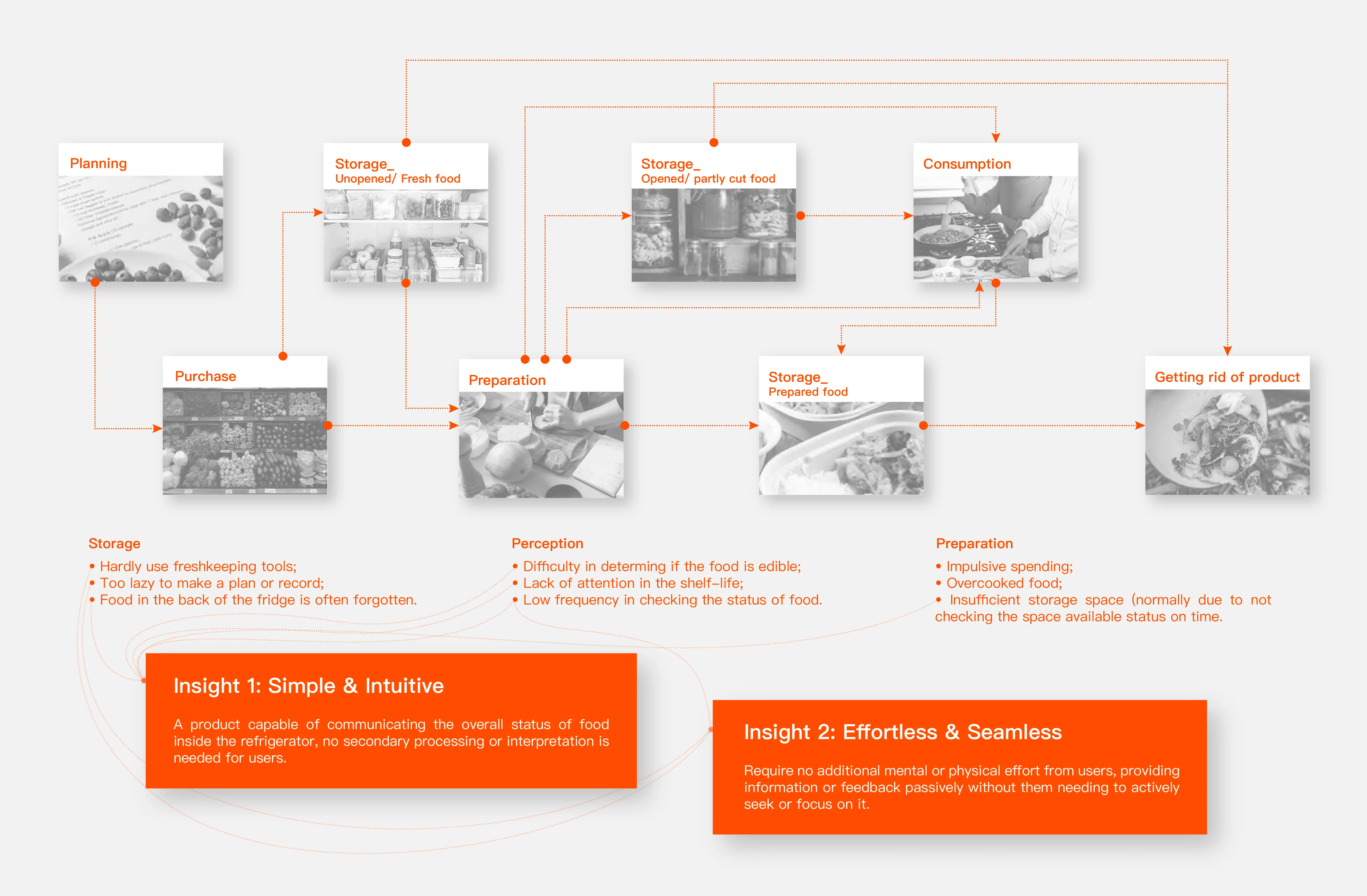

These data also revealed two critical insights for the later prototype development: 1. Challenges in food information perception: Users struggled to identify subtle spoilage or overcooked forgotten items, leading to waste. 2. Resistance to proactive management: While mindful users organized and planned, others found such efforts cumbersome, highlighting an "effort barrier."

These insights directly informed my design goal: 1. To create a product offering intuitive state representation—perceptible, external, and instantly understandable information; 2. And effortless & unobtrusive engagement, requiring no additional user effort or focus.

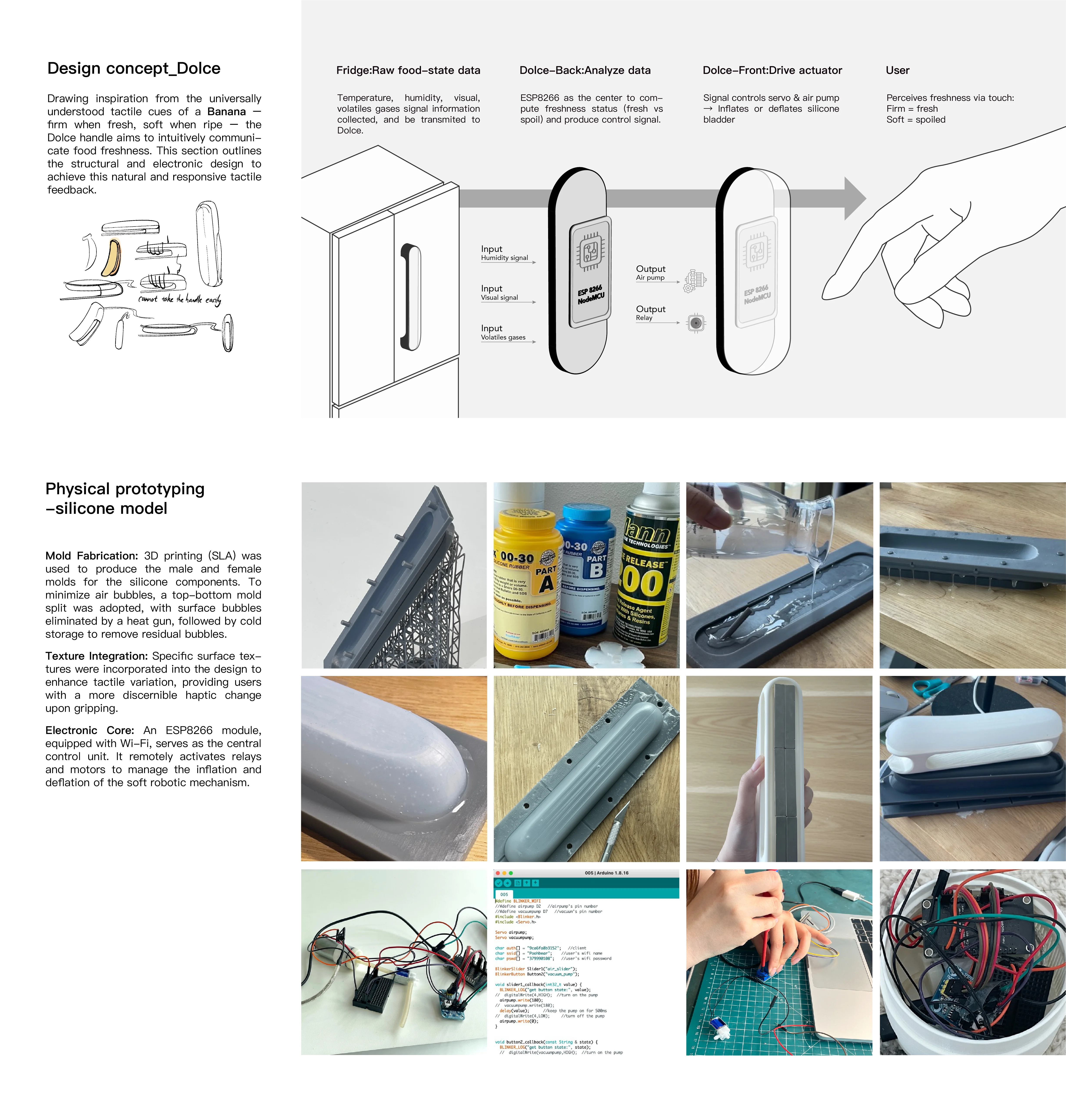

To address the inherent information blockage of a refrigerator, I posed a fundamental question: How can we convey changes within a completely sealed 'black box' (representing the fridge) to someone outside, without direct visual access? This led me to explore various sensory cues, mimicking natural indicators of spoilage like mold, smell, or changes in texture. From these insights, I composed three concepts. Following an evaluation across four key dimensions—User Cognitive Load & Behavioral Effort, Sensory Intrusiveness, Research Feasibility, and Action Prominence/Immediacy—I selected Dolce, a tactile interaction approach, as the design direction for this project.

To realize a prototype capable of dynamic firmness changes, I explored various methods, including phase-change materials and soft robotics. Given the constraints of time and fabrication complexity, soft robotics was chosen for its material accessibility and maintainability, leveraging air pressure changes to alter the handle's softness and rigidity. Thus, the concept of Dolce was created.

At the commencement of each food storage cycle, users load newly purchased fresh ingredients into the refrigerator. Built-in visual and olfactory sensors automatically capture food data, prompting Dolce inflation. The refrigerator handle exhibits a firm, full tactile sensation, metaphorically representing the fresh condition of all stored food items.

When Dolce detects spoiled food or items that have been stored for too long, the inflatable silicone chamber on the handle deflates and collapses. As the user opens the refrigerator, they immediately perceive the tactile change. In this way, the warning information about food spoilage passively flows into the user’s mind. The user can then conveniently check which items are about to go bad and consume them in time. This approach eliminates the need for users to frequently and proactively check the refrigerator or a mobile app on a fixed schedule.

In conventional smart refrigerators, food-status alerts are pushed to users’ smartphones via apps. These notifications often appear at inconvenient moments—during work hours, commuting, or outdoor activities—making them easy to ignore or forget by the time users return home. As a result, spoilage warnings lose their effectiveness, and users are unlikely to check the fridge proactively.

DOLCE embeds the notification directly into the user’s action of opening the refrigerator. This passive form of information intake requires zero additional time or effort from users. More importantly, its immediacy enhances actionability: users receive the spoilage cue precisely when they are already in front of the fridge and can address the issue instantly.

Given the time and resource constraints, the 'Wizard of Oz' method was employed to simulate Dolce's intelligent functionality for user validation. Our setup involved a Fridge camera to remotely monitor food status. A Researcher then manually simulated AI detection of food spoilage, consequently remotely controlling Dolce's air pressure to trigger its tactile feedback, thus conveying the food's status interactively to the user. The experiment unfolded over two weeks, engaging three households (five participants in total) in staggered probe studies and post-experiment interviews, allowing for a longitudinal assessment of Dolce's impact on food waste behavior.

Building directly upon the tactile explorations in my Dolce project, I began to ask: If haptic interaction were integrated into other aspects of the smart home, could it make information feedback more intuitive and 'warmer' for humans, seamlessly blending into daily life rather than just displaying or vocalizing data and text?

For instance...

Numbers rarely speak to me. When my smart home panel tells me “the room is 13°C,” I still have no idea what that actually feels like. I have to search online for outfit suggestions, or crack open a window to sense the air myself—an unnecessary hassle when the weather is extreme.

So I began to imagine: what if the smart home itself could let me feel the temperature? A central interface that doesn’t just display information but conveys it through touch—immediate, human, and instinctive.